I spend a lot of time thinking about how our government does business. I also think about the way the public debates the issues and how we are informed (or become uninformed). And I think a lot about how bad things have gotten and how they are getting worse.

I spend a lot of time thinking about how our government does business. I also think about the way the public debates the issues and how we are informed (or become uninformed). And I think a lot about how bad things have gotten and how they are getting worse.

Several times I’ve said or written: “This is the most contentious time in history.”

Never has anyone disagreed with that statement no matter which side of the political fence they stand.

Sit down for this.

What if I said…?…our dialogue is not getting worse. The political climate that we are living in today might even be…better than it was.

What on earth am I talking about?

I enjoy reading history, but find myself having to look beyond conventional history that has, for over two centuries, woven fairytales around the creation of America. From what we’ve been taught in school and from the traditions we’ve brought into American life, stories and those who created them, were beyond reproach and founding visions were clearly defined. But as I dig deeper into autobiographies and historical records, a more interesting perspective begins to develop.

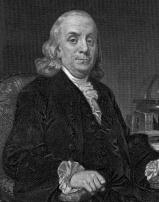

No less than Benjamin Franklin expressed his regret for the growing animosity and “false accusations” that Americans have toward each other, toward their government  and even toward “our best national allies.”

and even toward “our best national allies.”

While we have myriad resources today to retrieve or disseminate information and ideas, the central theme of our most contentious debates is the same. Franklin wrote 250 years ago: “In the conduct of my newspaper (Poor Richard’s Almanac) I carefully excluded all libeling and personal abuse, which is of late years become so disgraceful to our country.”

At the founding of our country and for nearly the century that followed, states bargained with other countries, and fought over where state borders should be. Not with rhetoric and loquacious debate, but with muskets, swords and pistols.

Much has been written about the contempt that our present Congress appears to hold for members from the other party, but they seem to draw the line at verbosity. 150 years ago as Congress debated the Kansas Territory’s pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution, a Pennsylvania Republican and South Carolina Democrat exchanged insults, which soon turned into a brawl. More than 30 Congressmen from both sides joined the melee until the combatants were arrested by the Sergeant-at-Arms.

years ago as Congress debated the Kansas Territory’s pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution, a Pennsylvania Republican and South Carolina Democrat exchanged insults, which soon turned into a brawl. More than 30 Congressmen from both sides joined the melee until the combatants were arrested by the Sergeant-at-Arms.

Contempt was so high in the 19th century between states that actual border wars broke out. Do you know why Michiganders are called “Wolverines”? Because people from Ohio found them to be no different from the angriest, most foul tempered creature of the forest.

As they argued violently over a ribbon of land at their border called the Toledo Strip, blood was eventually shed and state militias were called to quell the dispute. A simple border between Americans, living no more than a few miles apart, led them to view each other as fundamentally different human beings.

As they argued violently over a ribbon of land at their border called the Toledo Strip, blood was eventually shed and state militias were called to quell the dispute. A simple border between Americans, living no more than a few miles apart, led them to view each other as fundamentally different human beings.

Things were no different west of the Mississippi when the Kansas-Nebraska Act repealed the Missouri Compromise. The Missouri Compromise created verbal and physical warring in territories where a line divided the north from the south, allowing slavery to be legal in new states below the line, and illegal above.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act was a compromise of that compromise and stipulated that the issue of slavery would be decided by the residents of each territory (known as popular sovereignty). After the bill passed on May 30, 1854, violence erupted in Kansas between pro-slavery and anti-slavery settlers, a prelude to the Civil War. Abraham Lincoln, considered by many to have been the greatest President in our history was reviled by both sides of this dispute.

Posters calling him a “tyrannical dictator” and a “traitor” were not exclusive to the South. One Chicago Times writer even reviewed Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address thusly: “The cheek of every American must tingle with shame as he reads the silly flat dishwatery utterances of a man who has to be pointed out to intelligent foreigners as the President of the United States.”

Posters calling him a “tyrannical dictator” and a “traitor” were not exclusive to the South. One Chicago Times writer even reviewed Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address thusly: “The cheek of every American must tingle with shame as he reads the silly flat dishwatery utterances of a man who has to be pointed out to intelligent foreigners as the President of the United States.”

I have no delusions that we have solved our dialectic dysfunctions and that gentle decorum is the order of the day, but today as we argue, yell, accuse, castigate, belittle, and protest each other, it would behoove us to consider what we don’t do any more in the practice of our political debates.

what we don’t do any more in the practice of our political debates.

We don’t fire across our state borders at each other over land disputes. Our states no longer act as sovereign entities, negotiating with foreign powers, to bolster their own interests against other states.

And while it is true that many people, along with pundits and politicians have said nasty things about speeches the President, the Speaker of the House, candidates, or any number of representatives have made, have any been more insulting than “silly flat dishwatery utterances”?

At the very least, this historical realization can bring us a glimmer of hope that better times lie ahead.