There sure is a lot of talk lately about that venerable old document we call the “Constitution.” There’s a lot of disagreement over how it is to be interpreted, and the intentions of the original Framers, but one thing everyone seems to  agree on is that no one is getting it right. Except for ourselves, of course, whenever we want to use it to enforce our views.

agree on is that no one is getting it right. Except for ourselves, of course, whenever we want to use it to enforce our views.

Our Constitution is the supreme law of the United States and defines the rules and separation of powers by which the three branches of federal government will operate. It is the charter that outlines how our government is to work.

Within the Constitution is Article 5 which defines the Amendment Clause; the process by which the Constitution can be changed. The first 10 Amendments are known as the Bill of Rights, however, 17 more have been added since. Article 5 was created because the  Framers, collectively visionary, knew that the world and their young country would change.

Framers, collectively visionary, knew that the world and their young country would change.

Thomas Jefferson was even more bold and wrote that every generation of citizens should analyze the constitution of their government to determine whether it truly serves the public`s needs. And he used this image to clarify his assertion: “Because as we grow older, as a republic, you cannot expect a man to wear a boy’s jacket.”

The Founding Fathers realized they could not foretell the evolution of American values, inventions and ethics and they knew that their charter, if it is to remain relevant, would have to have a process by which to reflect societal change and growth.

The 19th Amendment is one of the clearest realizations of that necessary Constitutional function.

The 2nd Amendment is the only amendment that states a purpose and that is to protect the security of a free state. But the meaning and relevance of a “well-regulated militia” will forever be questioned, leaving the 2nd Amendment like a middle child; a little too social and a little too vague.

The 2nd Amendment is the only amendment that states a purpose and that is to protect the security of a free state. But the meaning and relevance of a “well-regulated militia” will forever be questioned, leaving the 2nd Amendment like a middle child; a little too social and a little too vague.

The one that I want to talk about here is their oldest sibling:

The 1st Amendment.

This addendum is the one that holds the most latitude and relevance in understanding our Constitution. The First Amendment prohibits the making of any “law respecting an establishment of religion, impeding the free exercise of religion, abridging the freedom of speech, infringing on the freedom of the press, interfering with the right to peaceably assemble and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

The Framers quickly realized after constructing the parameters for representative government that the principles by which it would govern would have to be as resolute. Opposition to the ratification of the original Constitution was due to a concern for the lack of guarantees regarding civil liberties and the First Amendment, thereby, established fundamental rules to protect individual freedom.

It made clear that we must be free to worship (or not to worship) as we please, that the state cannot restrict the elocution of the mind to express ideas (including a free press), and finally, it sets the stage for a redress of grievances so as to secure the power of the people within that government.

Religious freedom is the tenet that is most often discussed these days, but it is Freedom of Speech that stands at the center of our agreements and our  misunderstandings.

misunderstandings.

It was recognized as a “Universal Declaration of Human Rights” when that was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948. Meaning that (according to the UN’s Article 19) the right to speak one’s mind is an unalienable right of all people.

There is a gray area, though. “Libel, slander, obscenity, sedition (inciting ethnic hatred, for example), copyright violation, and revealing classified information” are not included, leaving us with a vulnerable understanding. Who is free to say what and to whom? Who owns an idea? What is the line that libel or slander must cross to impose upon another? What is obscene and who determines it? Are we free to hate? Can we assemble others to join, and how far can we go to further that cause?

When the American Nazi Party petitioned Skokie to stage a march was that an exercise of free speech or sedition?

Unfortunately, objective clarity will never exist, but what we can do is investigate why freedom of expression must be upheld.

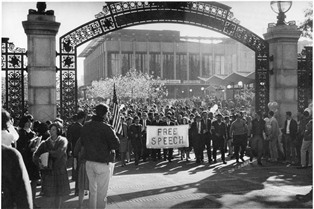

One of the greatest examples of Free Speech consciousness began in 1964 at the University of California’s Berkeley Campus.

The seeds were planted back in 1958 when Berkeley students formed SLATE as a political party to support Civil Rights, also creating a climate of awareness regarding student’s rights, and when the Berkeley establishment declared in 1964 that strict rules prohibiting advocacy of political causes or candidates would be enforced, the campus erupted.

A young man named Mario Savio was part of a crowd that had gathered as a former student named Jack Weinberg was arrested for manning a table for the Congress of Racial Equality outside Sproul Hall. The University police had just put him in a police car when Savio emerged from the crowd and yelled, “Sit down!” so that the car would be blocked.

A young man named Mario Savio was part of a crowd that had gathered as a former student named Jack Weinberg was arrested for manning a table for the Congress of Racial Equality outside Sproul Hall. The University police had just put him in a police car when Savio emerged from the crowd and yelled, “Sit down!” so that the car would be blocked.

Savio then climbed on top of the police car to give the most inspiring speech in the history of the Free Speech Movement; the last 85 words became legendary:

“…There’s a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can’t take part! You can’t even passively take part! And you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels…upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you’ve got to make it stop! And you’ve got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it, that unless you’re free, the machine will be prevented from working at all!”

Savio capsulized the essence of our cornerstone Amendment, from free speech to a redress of grievances: “And you’ve got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it, that unless you’re free, the machine will be prevented from working at all!”

The People have the power, but only if we exercise that power. We must have the authority to speak our minds, we must covet our individual liberties and challenge the forces that try to contain them. That also means people who offend, people who harbor hatred and ignorance, have that authority, but as Savio eloquently expressed – absolute freedom is what can moderate the will of the machine.

The machine can become tyranny and the freedom to express ourselves and to stand up for our rights is the only force with the aggregate strength to overcome it.

A few years ago I made a pilgrimage to Berkeley to see Sather gate and Sproul Hall where the Freedom of Speech Movement began. I stood in awe as I imagined the passion and conviction of Mario Savio and others who created a movement that clearly reverberates to this day.

A few years ago I made a pilgrimage to Berkeley to see Sather gate and Sproul Hall where the Freedom of Speech Movement began. I stood in awe as I imagined the passion and conviction of Mario Savio and others who created a movement that clearly reverberates to this day.

And what struck me is that it hasn’t changed. The trees have grown but the student’s tables with causes and speakers inviting passersby to join clubs and rallies to support equal rights, environmental issues and First Amendment freedoms, still line the path.

We are corroding the principles of freedom by limiting its relevance in a political dogfight to define it according to specific agendas.

relevance in a political dogfight to define it according to specific agendas.

We become strong only if we respect the freedom our Constitution protects, not simply by stating our entitlement to it, but by recognizing the challenges and responsibilities that come with it.

To put our bodies upon the gears.