We hear more and more debate about the size of federal government and what powers have been drained from the states in contrast. The argument from Republicans and Libertarians, in particular, is that the powers of the federal government have expanded beyond its constitutionally outlined parameters and that state governmental authority has been diminished.

Their argument is that we need to reverse this trend and restrict federal jurisdiction while enhancing state and local focus.

I’m not going to argue with that statement. I believe we have allowed for too lenient a definition of federal powers and have diminished the scope of localized governments. While making that statement, however, I am adding that this trend has been a consequence of our history and our own human nature.

In order to better define (and control) government responsibilities, we need to look at the historical context and at the characteristics that have brought us here.

At the beginning of our nation being an “American” was a vague concept and although there was clearly a spirit of nationalism, having defeated the British for our independence, it was less significant a proclamation to be an “American” citizen of the newly formed United States, than it was to be a “Virginian” or a “Pennsylvanian” for example.

At the beginning of our nation being an “American” was a vague concept and although there was clearly a spirit of nationalism, having defeated the British for our independence, it was less significant a proclamation to be an “American” citizen of the newly formed United States, than it was to be a “Virginian” or a “Pennsylvanian” for example.

Patriotism was more associated with the colonies of farmers who framed regions with state borders served by local, communal interests than centralized government. In fact, it was inconceivable in our infancy that a strong, centralized government would ever be necessary beyond the formation of a national army to defend alongside the local and state militias. This began to change when soldier-farmers returned home from the war for independence and many of them found their farms gone from unpaid taxes levied by the state to pay war debt.

Soon, citizen-revolts began within our still vulnerable country and the Constitution was written. Our Founders realized that a central government must be strong enough to maintain a balance of power between states and could not function if it relied solely on the states for revenue. Congress was, therefore, given the power to collect “taxes, duties, imposts and excises, to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States.”

Then, only 30 years after the establishment of our sovereignty, came the War of 1812…

1812…

War has a way of shaping our understanding of ourselves and the United States declared war as a result of long simmering disputes with Great Britain, specifically the impressments of American soldiers by the British.

The War of 1812 established once and for all the independence of the United States, and saw the emergence of strong nationalism. The British burned Washington to the ground and alongside the rebuilding of our capital city grew our national pride. Now we were a nation, not fighting for our creation, but defending our sovereignty. The strength of the national army, unified patriotism, and common purpose among the citizens of every state became relevant.

It was the Civil War that cemented into our collective psyche the value of having a strong Union beyond the individual sovereignty of states. Less than a century old, the United States faced its greatest crisis.

It was the Civil War that cemented into our collective psyche the value of having a strong Union beyond the individual sovereignty of states. Less than a century old, the United States faced its greatest crisis.

The brutal, post-war reality of Americans having fought Americans, and the resolve to preserve the Union, erased state allegiances as our sovereign identity and we were Americans first. We (well…white northerners, anyway) emerged with a concept of strong federal government.

The Civil War marked the greatest transition in American national identity and the ratification the 14th and 15th amendments that followed settled the basic question of citizenship. Under these amendments, it was now clear that anyone born in the United States and subject to its jurisdiction was a citizen, regardless of ethnicity or social status (sadly, and inexcusably, Native Americans were not included); we now had a portrait of an “American.”

Academics have long questioned when, precisely, federal government started growing, but can cite that before WWI federal government spending consumed less than 5 percent of the Gross Domestic Product. While Roosevelt’s New Deal is often viewed as the beginning of Big Government, it was really only the continuation of what was a growing trend that started in earnest right after WWI. The steadiest growth of government can be traced to the ratification of the 19th Amendment.

Polls have almost always shown that women, as a group, vote differently than men, and a gender gap issue is that of smaller government and lower taxes versus the expansion or creation of government programs to improve society.

Women have been more supportive of Medicare, Social Security and educational expenditures. Also, given the fact that a woman’s average income has been historically lower and less likely to vary over time, there is incentive to prefer more progressive taxes.

That is certainly not an indictment of women for increased spending, and it is not a sweeping generalization of women’s desires, or men’s for that matter; the intent is to show the inevitability of expansion in the natural evolution and realization of equality.

As our understanding of liberty and inclusion grows, so will the interests of Americans, and the safeguards we must provide.

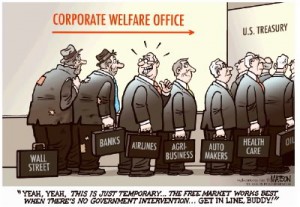

There are several discussions that we should be having before this debate about the size of government and what expenditures can or cannot be cut. We should be talking about production and the creation of jobs. We should be asking corporate America why they are not re- investing with expansion commensurate to profits and cash reserves which are, for many, at all time highs.

investing with expansion commensurate to profits and cash reserves which are, for many, at all time highs.

We should be looking at welfare programs and adjusting them to critical but fair standards of compliance, but we should also be talking about the Americans that welfare and educational programs enabled to return to work.

And there is an important matter of a more philosophical nature for all of us to consider: Government is what we made it. It exists in whatever size it exists because of what we have demanded from those we elected to protect our interests.

Government has evolved alongside the progression and realization of the ideals of freedom and representative democracy. Yet it also must be managed and contained to operate efficiently with only growth that benefits our Republic. When we consider what part of government is overreach and where it may be deficient, we must first look to its largest branch: The 315 million people federal government represents.

Our part as citizens is to participate in the process that is part and parcel with maintaining this representative system. That is the call to action. The necessary conversations do not start in Washington but, rather, in our kitchens and at our neighbor’s barbeque. Are we educating ourselves beyond our biases? Are we offering the service that is demanded from us, individually, in order for a free society to survive? Are we giving back?

When we examine ourselves, then, and only then, will we begin to find better leadership to control the reins of power that often corrupt and misguide our politics.

When we examine ourselves, then, and only then, will we begin to find better leadership to control the reins of power that often corrupt and misguide our politics.

Let us be reminded of a great pledge offered over 60 years ago from a Democrat who embraced a tenet of a once Republican ideal: “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.”

That was not a call from President Kennedy to diminish government, it was a call for participation in government, with compassion and personal responsibility, from those of us who are capable, so that better government can prevail for us all.

Some interesting reading on spending that regularly updates: http://www.usgovernmentspending.com/us_20th_century_chart.html